By Laura Twomey

Wikileaks, now wellknown as a secretive organisation, have provided the raw documents behind some of this summer’s most controversial headlines. It is clear that Wikileaks is another facet in the growth of online journalism. They publish highly classified documents, otherwise inaccessible to journalists and the public at large, whilst protecting the anonymity of their whistle-blowers, who are often always in highly sensitive positions within their respective organisations. The site has been added to the US Department of Defense’s list of enemies “threatening the United States”.

Yet Wikileaks claim they merely provide a public service to potential whistle-blowers. The site has become a media circus on it’s own terms. Due to it’s highly sensitive nature, the short history of the site reads like a Le Carré novel, incorporating secret military documents, whistle-blowers and encrypted secrets.

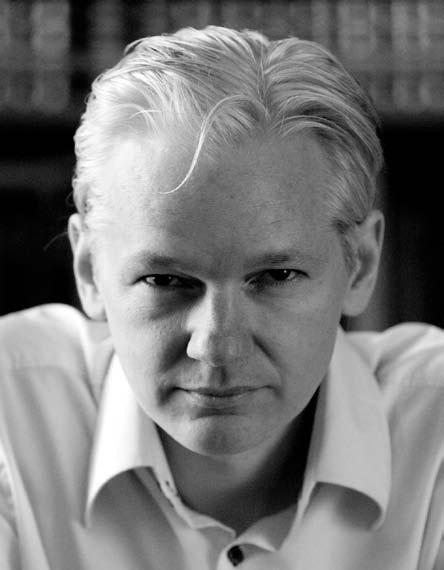

Add in a mysterious director and site editor, the inscrutable Australian Julian Assange. Making the rare public appearance, he allegedly lives out of a suitcase, and is currently embroiled in a sex scandal. When the first reports of his being questioned on suspicion of rape and sexual assault in Sweden arose last month, he was one of the first to cry conspiracy on his Twitter feed. Already there are whisperings of plans to oust him by other board members of the site. Surely Mr Assange, being their public face, cannot be doing wonders for their already shaky PR.

It all makes for a recipe of pure intrigue. Although declared by Time magazine as poised to become “as important a journalistic tool as the Freedom of Information Act” in the US, are things beginning to turn sour in the camp of online freedom?

The team behind the site claim that Wikileaks, launched in 2006, has released upwards of 1.2 million documents online. The site has flirted with controversy since then, having published details of an email account belonging to Sarah Palin, a highly sensitive list of members of the BNP and various US intelligence documents relating to Guantanamo Bay.

Yet the real bombshells were dropped this summer, when Wikileaks posted more than 76,900 records of incidents and intelligence reports about the Afghan war on its website, providing a devastating portrait of the war. You could argue that a new era in online journalism had been forged following the biggest leak in US history, with the suspected whistle-blower being hailed as an antiwar hero by many. Traffic to the site doubled within one week.

They revealed how coalition forces have killed hundreds of civilians in unreported incidents and how NATO commanders fear neighbouring Pakistan and Iran are fuelling the insurgency. A “Collateral Murder” video of a US Army Apache attack helicopter mowing down people in Baghdad in 2007 also caused huge embarrassment for the US government and prompted a worldwide outcry earlier in the year. The site has undoubtedly staged some spectacular scoops in the last couple of months, which have left the US Department of Defense and other public bodies desperately chasing the trail of a new and interminable threat regarding information security and secrecy.

The concept of Wikileaks and their stark expositions seem to continuously divide pubic opinion. The site undoubtedly has its supporters, championing free speech. Among those supporters is Michael Moore, no stranger to controversy, who recently donated money towards the defence team of the suspected whistle-blower of the Afghan diaries. Even Fidel Castro has voiced his approval for the site. In an interview with the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, he stated the internet ‘has put an end to secrets…. We are seeing a high level of investigative journalism … that is within reach of the whole world.” He believes the internet “is the most powerful weapon that ever existed”.

With the site revealing numerous human rights violations committed by the United States abroad, and the US Government violating many international laws in the Middle East, surely this transparency should be welcomed? Yet, 61 percent of Americans consider the release to be an act of treason. In an open letter to Wikileaks, Reporters Without Borders said: “The precedent you have set leaves all those people throughout the world who risk their freedom and sometimes their lives for the sake of online information even more exposed to reprisals.” Reporters Without Borders, self proclaimed protectors of international press freedom, have accused Assange of “incredible irresponsibility”.

Despite their detractors, those behind the organisation may be prepared to release more sensitive information if authorities interfere with them. The Pentagon want them to pull back the Afghan war diaries already posted on the Internet. Yet there is also an encrypted “insurance” document available, containing more sensitive information, which has been downloaded thousands of times. This tactic displays technology is allowing the site to be an unstoppable force, an unpluggable leak. Any fight, even by the Pentagon, will prove to be futile, while the file lies dormant on thousands of desktops.

Assange, while still in his capacity as director, has pledged to fight on, and release more raw data, once it has been verified. Who knows where this story will go in the next few months? US Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor has already predicted the question of free speech versus illegal speech concerning Wikileaks will probably come before her during her tenure.

So the question remains: can Wikileaks survive the growing pressure towards their transparent practices and the developing controversy surrounding Assange? Is there a point where transparency and information regarding governance can just go too far when the question of national security is at risk? One thing is clear – the information wars are undoubtedly going to shape the next few decades to come.