DIVINE worship was once an integral part of college life. An early 18th-century English translation of the college’s statutes allows us to see how this was so, with its detail on the routine of prayers here.

Robert Bolton’s 1709 translation gives the college’s schedule of supplication: “Prayers shall be publickly offered up to God in the Chapel thrice every ordinary day, at the six of the clock in the morning, afterwards at ten in the forenoon, and lastly at four in the afternoon.”

There was to be a sermon on Sunday mornings, with an exception: “Except, that on the Sundays in Lent, we will and ordain, that the Provost, Fellows and Scholars, and all the students dwelling in the college, shall solemnly go to the cathedral church of St Patrick, and there have a sermon, but in the afternoon, according to the ancient practice of the church.”

The correct get-up was prescribed, with a penalty of five shillings for transgressors. All attending wore “clean surplices, and (as many as are graduates) with hoods proper for their degree”.

These ancient college statutes record Trinity College’s unique and peculiar prayer, which was recited in English: “O Lord Jesu Christ, who art the eternal Wisdom of the Father, we beseech thee to assist us with thy heavenly Grace, that we may be blessed in our studies this day, and above all things, may attain the knowledge of three, whom to know is life eternal; and that, according to the example of thy most holy childhood, we may grow in wisdom and years and favour with God and Man. Amen.”

This prayer, which alludes to Luke 2:52, was later incorporated into the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of Ireland, to be used “in colleges and schools”. The old statutes did not tolerate dissent – particularly of the Catholic kind. “The Provost and Senior Fellows”, read the document, “shall take care that no Popish or heretical opinion be maintained or abetted within the limits of the college.”

It continued: “Moreover, no one shall be elected Fellow, who shall not, by a solemn and public oath, renounce the Popish religion, as far as it differs from the catholic and orthodox faith, and the jurisdiction of the Pope of Rome.”

These sentences reflect the sentiments of Archbishop Laud, the Archbishop of Canterbury in the mid-17th century, according to Dixon in his 1902 history of the college. Despite the clauses, Dixon writes, no students were required to make religious declarations on matriculation, and even those living in rooms were not forced to attend services if known to be dissenters of some kind.

Nonetheless, while the Catholic student could get through a few years in college, the oath against Transubstantiation at Commencements would have prevented him taking a degree, until it was removed in 1795.

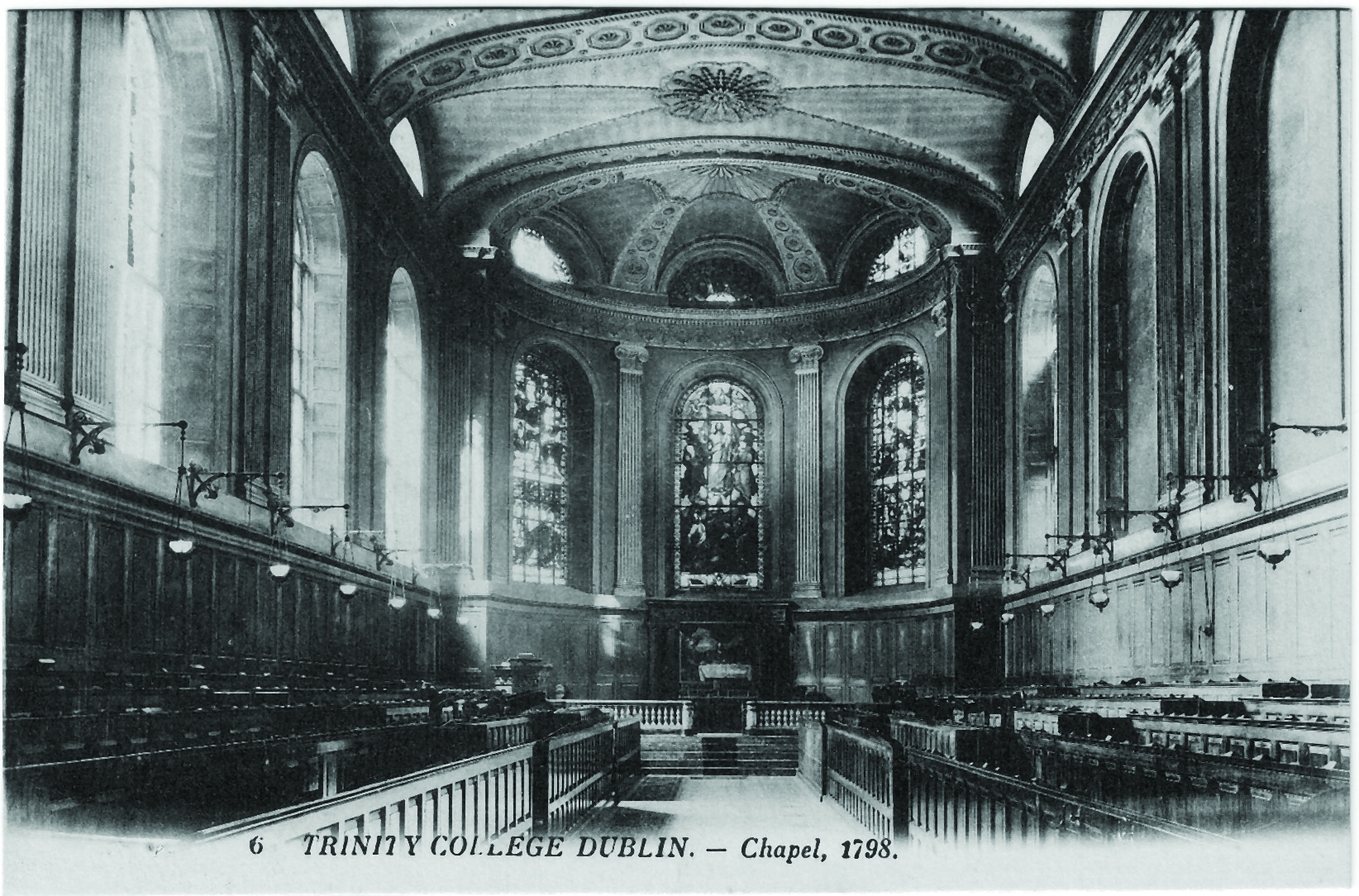

Catholics nearly won the day in 1689. When King James II’s soldiers took over the college, the chapel – not the present building, which was finished in 1798 – was turned over to Catholic worship. On October 21 that year “the chapel was sprinkled and new consecrated, and Mass was said in it”. But that situation was short-lived. That year may have been the last in which Mass was said publicly in college using the ancient Roman rite – today the missal of Paul VI is used.

A detailed study of the liturgical life of Trinity in years past would be a worthwhile endeavour. In the meantime, these references and some pages in Lesley Whiteside’s The Chapel of Trinity College, Dublin (1998) give some insight.

THE UNIVERSITY of Dublin Calendar is admirable in its pedantry but irritating in its omissions. Why do the committee members of the Graduate Students’ Union have no postnominals? Are we to take it that this year’s committee is not made up of graduates?

Similarly, again, the members of the Scholars’ Committee do not have “Sch” appended to their names , yet the CSC “chair” (read chairman, unless he is an item of furniture) correctly does. The Students’ Union’s communications officer lacks his – along with others, no doubt.

I must repeat another complaint. The editors of the Calendar have jumped on the minimalist buzz about 30 years too late. The change to Arial is jarring and unnecessary. Next year, switch back to Times – or, much better, to the Century variant used before 1980.

A HERALDIC snippet. The awarding of degrees is the main function of the University of Dublin, as distinct from Trinity College. One would think, therefore, that the coat of arms of the University of Dublin would have been seen on degrees of this university from the time the arms were granted in 1862. However, on October 24, 1963, Trinity News recorded that they were not used until that year:

“One hundred and one years after a coat of arms was granted to the University of Dublin, they were first used on the degree certificates. The first person to receive one of these was JF Kennedy, President of the United States, who had conferred upon him an honorary degree of doctor in laws in St Patrick’s Hall, Dublin Castle, on June 28, 1963.”

pehenry at tcd.ie