Why did Michael Stone cross the road? To look at the conflict arising in Nepal over the construction of a road in the untouched Annapurna Conservation Area, compromising one of the world’s greatest treks, the Annapurna Circuit.

The Annapurna Conservation Area spans 7,629km2 of Nepal’s northern frontier, making it the largest protected area in the country. The area consists of five districts which share the immense Annapurna Himal, home to Annapurna I, the tenth highest mountain in the world. With a climate ranging from tropical to alpine and housing a melting pot of Tibetan, Hindu, and indigenous cultures, the area has become a hotspot for Himalayan adventures.

The majority of people venture to the Annapurna to embark on the famous Annapurna Circuit trek, heralded as one of the greatest in the world for its breath-taking views of three 8,000m peaks. This summer I joined their ranks. A friend and I were keen to visit the distant Himalaya and I set about finding a suitable trekking destination. Upon researching the area I came across a veritable sea of contention.

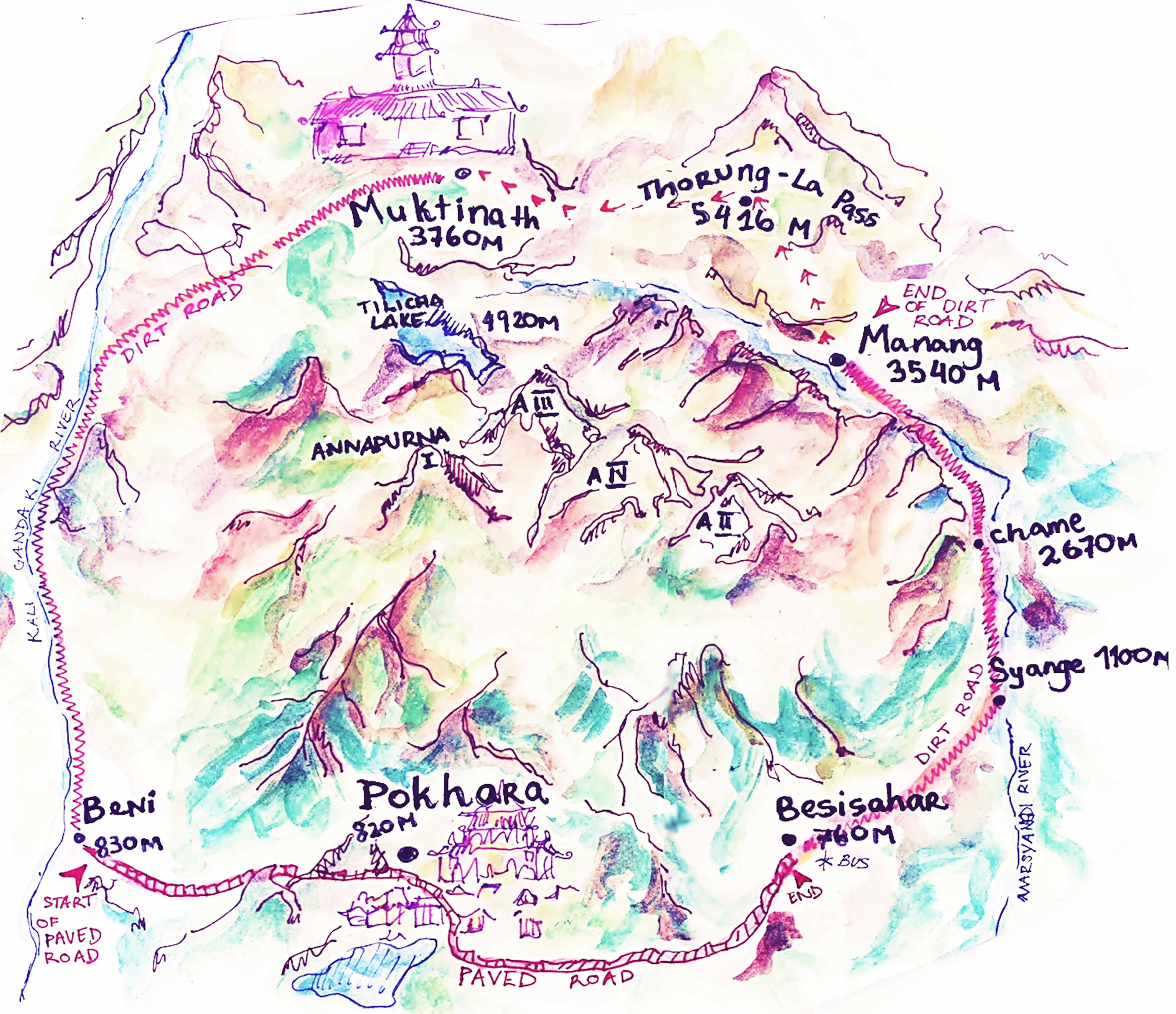

The source of the controversy is the construction of a road along the same route as the trek, following the Marsyangdi River to the east and the Kali Gandaki to the west. For travellers, the road represents the ruination of a preserved and relatively untouched part of the world but for the 100,000 inhabitants of the conservation area, it represents progress and an increased standard of living. The majority of blogs and travelogues I perused concluded with a plea: “go now, before the road is completed.” I resolved to follow this advice and Aidan was more than happy to join me. Making this decision ultimately allowed us to determine, first hand, our position on the road (no pun intended).

Arriving in Pokhara, Nepal’s second biggest city and gateway to the Annapurna, we heard stories of the road from those returning from the trek and speculation from those setting off with us. The myriad of varying tales meant that the only way to find out how far the road stretched was to suss it out for ourselves. We boarded a bus to Besisahar, at the edge of the conservation area, which marked the end of the paved road, and spent a night there in wait of an early bus the next day.

Once the traditional starting point for the trek, the extension of the dirt road has rendered Besisahar a glorified bus depot, a purgatory of sorts. Here we learnt that it was possible to take a minibus as far as Syange, 26km into the traditional trek, for 600 rupees (¤5). We also discovered that jeeps ventured as far as Chame, 56km into the trek, for 2500 rupees (¤21). One hardy driver was willing to face the 22 hour slog to Manang, skipping 90km of the trek for 4000 rupees (¤35).

We decided to board the bus to Syange in order to escape the hinterland of Besisahar. From there, we trekked to Manang in four days where we found the dirt road did indeed end, giving way to a trail that took us to the pinnacle of the circuit, the Thorung-La pass at 5,416m, in two and a half days. Descending to the other side, we stumbled into the town of Muktinath. As a Hindu pilgrimage site, it was given priority when construction started on the road and it is now possible to travel by bus all the way to Pokhara in one day, with as little as two stopovers.

“The source of the controversy is the construction of a road along the same route as the trek, following the Marsyangdi River to the east and the Kali Gandaki to the west. For travellers, the road represents the ruination of a preserved and relatively untouched part of the world but for the 100,000 inhabitants of the conservation area, it represents progress and an increased standard of living. The majority of blogs and travelogues I perused concluded with a plea: “go now, before the road is completed.” I resolved to follow this advice and Aidan was more than happy to join me. Making this decision ultimately allowed us to determine, first hand, our position on the road (no pun intended).”

Once this was made known to us at the makeshift bus stop just outside Muktinath, it really struck me just how extensive the road had become. It was now possible to travel 179km of the 210km circuit by road and hike only 31km from Manang to Muktinath. What was once a 21-day trek has been cut to a potential three. In fact, it occurred to me that it would be theoretically possible to get a bus to Muktinath, ascend to Thorung-La in the early morning and descend all in one day.

This poses issues far more severe than the most common argument against the eyesore the road presents. My first concern is for trekkers who attempt the Thorung-La after skipping the trek to Manang or Muktinath. Travelling from Besisahar to Manang presents an altitude gain of 2,780m; Pokhara to Muktinath is 2,940m. Such a gain in as little as a day far exceeds the recommended 300-500m. If people were to press on without acclimatising, they would leave themselves vulnerable to AMS (acute mountain sickness), or worse, HAPE/HACE (high-altitude pulmonary/cerebral edema), whose immediate symptoms are not unlike the headaches of AMS but without a descent of at least 1,000m, they may lead to paralysis and death. The accessibility to higher altitudes offered by the roads may attract inexperienced and unprepared individuals who would be more susceptible to these illnesses.

Also of concern are the residents of towns bypassed by the road. With less traffic stopping along the way, a key source of income is set to dry up. One of our companions went so far as to suggest that in the not so distant future he could see a Four Seasons opening up in Manang, where the wealthy could drive/fly to and do a few side-treks before crossing the Thorung-La into Muktinath and then heading home, all in the space of a week.

Manang and Muktinath are set to become tourist hubs and those in villages further down the trail will have to fill the gap left by trekkers by either migrating to the bigger towns or selling their produce to them. There will be further trouble for those who work as guides and porters in the lower regions as jeeps and buses begin to take their place.

The inhabitants of these towns overlook this particular point as they welcome the road, seeing it as a symbol of progression. Granted there are some who resent the mark it makes on the valley wall but the majority are in favour. The fruits of the road are plain to see. Snickers and Coke are available in Manang and Chame for little over the price paid in Pokhara and Kathmandu. The owners of teahouses have access to satellite television, and some guesthouses in Muktinath have free WiFi. These luxuries have only become available of late, some as recently as in the past year. I was pleasantly surprised and indeed a little amused at some of them but for the locals they represent a revolution. This is epitomised in the gang of family and friends who gathered in our guesthouse in Manang to watch Bollywood movies and Indian Idol Junior, and by our host in Syange, who proudly showed us how to access data on his smartphone. On a more fundamental level, the journey to Pokhara for these residents is no longer a week’s undertaking or an unaffordable helicopter ride; it can be achieved within the day. This improves their standard of living in giving them access to the luxuries described above and essentials such as better healthcare and education. On this front there is no doubt that this road is relieving people of a basic life, a potentially stagnant existence, and propelling them into the 21st century. But what of their land, savoured by outsiders for being so wistfully akin to a time long before our own? From my own experience, I would say that the landscape has undoubtedly changed; the explosions that cleaved through the mountainside to make way for the road have left a scar that snakes along the edge of the valley. Though not exactly pleasing to the eye, it’s not quite the eyesore it’s made out to be. I would argue that the Annapurna is so vibrant and breath-taking that it is easy to forget the road is there.

The road also opens up avenues that were once unavailable for the average trekker. Aidan and I made a side trek to the spectacular Tilicho Lake, the highest in the world, and this involved staying in a guesthouse built, quite haphazardly I will admit, on a camping ground. If not for the extension of the road to Manang, it wouldn’t have been worthwhile to bring the required plywood as far as Tilicho. Doors have been opened to wonderful places off the beaten track by virtue of its very existence, and the view is no less magnificent off the traditional circuit.

Because both sides of the argument can appear to be justified, the road will continue to be a contentious issue. Inhabitants are for the road as it brings the modern life they seek to their homes and visitors are against the road as it takes away from the traditional, simple culture and the inspiring vistas that house it. Ultimately the road will act as a catalyst for Western culture joining the melting pot that exists in the area. To those who want no hint of a road to interrupt their line of vision, I would say that it is possible to visit the Annapurna area and avoid it. It most certainly is not for us to rob the people of the Annapurna of the advancement coming up the road.